This report has been prepared as part of the Urban Institute's Assessing the New Federalism project, which has received funding from the Annie E. Casey Foundation, the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Commonwealth Fund, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the McKnight Foundation, and the Fund for New Jersey. Additional funding is provided by the Joyce Foundation and the Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation through a subcontract with the University of Wisconsin at Madison.

Keith Watson would like to thank Stephen Bell and Lawrence Thompson for their comments and guidance during the completion of this report, Kyna Rubin for her editorial assistance, and the numerous persons who provided comments on earlier drafts of this report.

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Urban Institute, its trustees, or its funders.

Devolution at the Federal and State Levels

The term "new federalism" describes the changing relationship between the national and state governments as they sort out their roles and responsibilities within the federal system. Devolution, one of the leading Washington buzzwords these days, is at the heart of the new federalism. Devolution entails passing policy responsibilities from the federal government to state and local governments. This process may include any combination of block grants to states, reduced grants-in-aid from the federal government, and increased flexibility for states in complying with federal requirements. The intent of devolution is to enhance the responsiveness and efficiency of the federal system, based on the theory that state and local governments can do a better job of providing services for citizens.

Since the start of the 104th Congress in January 1995, Congress has seriously considered proposals to convert Medicaid, welfare, child care, child protective services, and other programs into flexible block grants to the states. With the signing of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA) in August 1996, the federal government devolved to the states tremendous responsibility for public assistance to families with children. The new Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) block grant replaces Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), Emergency Assistance, and the Job Opportunities and Basic Skills program (JOBS). Under AFDC, the federal government provided open-ended categorical matching grants to states, along with guidelines for determining eligibility and payment levels. TANF gives states greater flexibility in designing their own public assistance and training programs for needy families with children. 1 However, TANF does stipulate federal mandates such as time limits and work requirements. The new law also combines federal child care funds previously distributed to states under three programs (AFDC Child Care, Transitional Child Care, and At-Risk Child Care) into a single Child Care and Development Block Grant. A primary goal of this change is increased flexibility for states in developing child care programs and policies.

As the federal government has shifted certain responsibilities to states, several states are similarly rethinking their policies in relation to local governments. Several states are considering or have already enacted proposals to increase the responsibilities of local governments in administering or funding certain government functions. This shift may occur in two ways. First, policy may be changed with the explicit intent to devolve responsibilities to local governments. For example, a state may enact legislation to shift funding and administrative responsibilities for mental health programs from the state to the local level. Second, additional de facto devolution may occur through decisions about state aid and other policies affecting local governments that do not explicitly seek to change state-local relations. For instance, a decision to reduce general state aid to local governments may be primarily intended to balance the state budget, but it has the indirect effect of increasing the burden on local governments for funding locally provided services.

A considerable amount of de facto devolution has occurred since the mid-1980s. This devolution is reflected in the relatively slow growth of state financial aid to local governments, 2 which is one of the reasons local taxes have been rising faster than state taxes almost continuously since 1985. 3 Other developments during this period included the granting by states of increased authority to impose local sales taxes and the gradual adoption of limits on states' abilities to impose unfunded mandates on localities. This period is characterized as de facto devolution because most of the changes occurred implicitly, as states assigned a low priority to helping local governments because of state budget pressures and became more willing to allow localities to handle their own problems without state interference.

In recent years, several states have moved beyond de facto devolution and have considered legislation explicitly intended to devolve responsibilities from state to local governments. Some states have considered converting certain existing state aid programs into block grants, transferring responsibility for the management of these programs to localities. Others have combined funding streams for local aid programs to allow for greater local flexibility or have adopted mandate relief efforts that provide localities with greater control over their budgets and provision of services. Despite the trend toward greater devolution, however, a few states have instead considered changes that would reduce or eliminate local involvement in program funding or administration while increasing the role of the state government.

Focus of This Analysis

This report describes some of the state legislation proposed or enacted in 1995 and 1996 that had the explicit intent of shifting program funding or administrative responsibilities between state and local governments. It covers only the areas of social services, public assistance, and workforce development; changes in other areas, such as criminal justice policy, are not considered. 4 Although changes in the amount of state general financial aid to localities (de facto devolution) can affect service provision in these areas, this paper focuses only on program-specific policy changes. Explicit devolutionary shifts of this type include replacing state categorical aid with a county block grant, decreasing state government funding responsibilities in certain program areas, and transferring program responsibilities from the state to counties.

States may also move in the other direction by assuming responsibility for a program previously run by counties or by increasing the share of state program funding. Other changes related to state-local relationships, such as the formation of local or neighborhood planning councils to improve service delivery, are not included in this paper because they do not directly reallocate administrative or financial responsibilities between state and local governments.

The changes discussed in this report are those that were considered or passed from 1995 to mid-1996, before the passage of the federal welfare reforms in PRWORA. This analysis provides a basis for comparisons over time as states restructure their public assistance programs under the new federal block grant system. The examples of state-local devolution described here suggest the types of changes that states may consider as they adjust to the new flexibility provided by federal welfare reform legislation.

This report is based on a variety of sources. In January 1996, all governors were asked to send to the authors their state-of-the-state messages, as well as state budget requests and any proposals involving state-local devolution. This information was supplemented by reports from other sources, such as surveys by the National Association of State Budget Officers and the National Governors Association, a review of state legislation by the National Association of State Legislatures, and a periodic newsletter from the National Association of Counties. 5 All the items from these sources were amplified by direct communication with executive and legislative branch officials in the states. Despite the considerable effort devoted to obtaining information on devolution-related proposals, this report is not necessarily exhaustive because the information collected by these surveys is usually incomplete. The report does, however, indicate the kinds of initiatives that have been proposed or enacted.

The first section provides a context for the discussion of state-local shifts by describing the historic level of local involvement in the administration of certain social services and public assistance programs. The following two sections describe enacted or proposed shifts in state and local responsibilities, first in the area of social services and then in the areas of public assistance and workforce development. A concluding section summarizes the findings and adds some general observations.

State-Local Administrative Authority

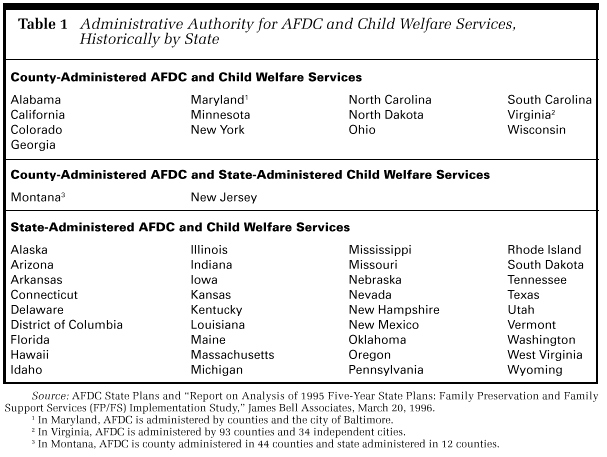

As a context for understanding state decisions concerning changes in state-local responsibilities, it is instructive to examine how those responsibilities generally are sorted out in each of the states. During the period of change examined here, states varied in the extent to which local governments were generally involved with administration, funding, and service provision in public assistance and social services programs. Describing the overall level of decentralization within each state is difficult because of the complexity of state-local structures and the lack of available information. However, it is useful to have some understanding of how involved local governments have been historically in each state. One simple and easily obtained measure of local government involvement is whether administrative authority for the old AFDC and child welfare services programs rested at the state or local level. Because federal laws required the same basic structure for AFDC and child welfare programs in all states, cross-state comparisons are meaningful. States were required to submit plans explicitly stating whether administration would be at the state or local level. Workforce development programs are highly decentralized in all states, so there is no simple measure of state versus local authority for those programs.

Table 1 shows three categories of states: those in which both AFDC and child welfare are county administered (13 states); those in which AFDC is county administered and child welfare is state administered (2 states); and those in which both AFDC and child welfare are state administered (35 states and the District of Columbia). This table provides an indication of the historic level of local involvement in public assistance and social services, but it does not capture the full complexity of state-local arrangements for these programs in all states. In Indiana, for example, AFDC and child welfare are state administered, but counties contribute substantially to funding for these programs. In Iowa, child welfare services are state administered, but many counties receive decategorized funding from the state that gives them greater local decision-making authority. Despite these and other exceptions, Table 1 makes an important distinction between states in which counties have traditionally played a large role in service provision and administration, and states in which those functions reside at the state level for at least two major programs. This will help to determine whether most of the shift in state-local responsibilities observed during 1995-1996 occurred in states with county-administered or state-administered programs.

Shifts in Responsibilities for Social Services

Social services include a large number of programs and funding sources at both the federal and state level. Programs that fall into this category include but are not limited to foster care and adoption assistance, child protective and prevention services (child welfare), assistance for homeless families, mental health services, substance abuse treatment and prevention, and teen pregnancy prevention. The following sections organize the state-local shifts in social services enacted or proposed during 1995-1996 into two categories: (1) child welfare, foster care, and adoption programs and (2) other social services.

Child Welfare, Foster Care, and Adoption Assistance

The primary federal funds for child welfare, foster care, and adoption assistance are provided by the Social Security Act under Title IV-B (child welfare and family preservation and support) and Title IV-E (foster care and adoption assistance). The level of decentralization for these programs is determined by the states and varies according to such factors as whether the system is state or county administered and whether localities share in program funding. In addition to federal funding sources (and required state matches of federal funds), states may provide their own funds separately for additional services and specify whether these state programs will be administered at the state or local level.

Only one major change in child welfare, foster care, and adoption assistance programs known to have been enacted during 1995-1996 devolved responsibilities from the state to localities. The New York Family and Children's Services Block Grant, enacted in 1995, converted state reimbursement for child protective and preventive, foster care, and adoption services into a block grant to local social service districts (the counties and New York City). This block grant provides a capped amount to local districts for these programs and requires local maintenance of effort at 80 percent of prior spending, but allows districts to create managed care programs to reduce costs. The block grant was funded at $428 million in 1995, a reduction of about $90 million, but roughly $80 million of funding was restored during the 1996 legislative session. 6

Several states considered but did not enact proposals to shift responsibilities for child welfare, foster care, and adoption assistance from the state to local governments. Perhaps the most ambitious of these proposals was made by Governor Pete Wilson of California in his 1995 budget request, which would have continued the devolutionary trend begun in 1991. At that time, California enacted a major realignment of state-local functions that shifted program and funding responsibilities from the state to counties for several mental health, public health, and indigent health care programs. That realignment also increased county funding shares for nine other health and social service programs. To offset the estimated $2.2 billion in new county funding needs, the state was expected to provide almost $2.1 billion in additional revenues to counties. However, because of the depressed California economy, revenue received by counties from the state fell considerably short of what had been projected when realignment was adopted.

The governor's 1995 proposals would have continued the 1991 realignment by transferring to counties complete financial and program responsibility for child welfare, child abuse prevention, foster care, and adoption programs. Counties would have been given discretion in determining service levels and service delivery methods, with limited state agency involvement. This realignment would have increased county costs by about $700 million, but the governor planned to compensate counties for a portion of this increase by assuming greater responsibility for court costs and by increasing state revenue allocations to counties. However, the legislature rejected the proposal.

One state proposed, but did not enact, a shift in responsibilities for child welfare programs in the other direction — from the local level to the state. The Indiana state legislature considered a bill in 1996 that would shift funding responsibilities from the counties to the state. The legislation would have obligated the state to reimburse 50 percent of county expenditures for child welfare services. In recent years, county contributions to total child welfare expenditures have exceeded 75 percent, while the state contribution has been only about 3 percent (with the remainder from federal sources). In addition, the bill would have eliminated the limit on county tax levies used to fund a number of welfare and child welfare services. However, the legislation would also have reduced state reimbursement for county AFDC expenditures from 60 percent to 50 percent, increasing county AFDC costs.

In summary, only one major state-local shift in the area of child welfare, foster care, and adoption assistance programs is known to have occurred in 1995 and 1996: New York's Family and Children's Services Block Grant, which changed state reimbursement to local social service districts from a state match to a block grant. In California, there was a proposal to shift complete financial responsibility for these programs from the state to the counties, but this was not enacted. And one state, Indiana, considered but did not enact legislation to shift costs for child welfare programs from the counties to the state.

Other Social Services

Aside from child welfare, foster care, and adoption programs, social services also include assistance for homeless families, mental health services, youth programs, substance abuse treatment and prevention, and teen pregnancy prevention. Federal funding sources for these services include the Social Services Block Grant, the Community Services Block Grant, and the Maternal and Child Health Services Block Grant. Because many programs are funded by federal block grants, states control the extent to which those funds are used at the state level or passed through to localities. States may fund additional services and determine for those state programs the level of program administration.

Wisconsin enacted changes in its Community Aids program in 1995 that consolidated several social services funding streams into a single allocation for localities. Community Aids are state and federal funds distributed to counties for social services for low-income persons and juvenile offenders and for services to persons with mental illness, substance abuse problems, or developmental disabilities. Counties are required to provide roughly a 10 percent match for funds received from the state. In 1994, $247 million of the $321 million in state and federal funds for Community Aids (77 percent) was provided as a basic allocation to counties for any Community Aids service. The remaining 23 percent of the funds was provided as 15 separate categorical allocations earmarked for specific purposes. The 1995 legislation combined many of the 15 categorical allocations with the basic allocation for a single Community Aids allocation. Five categorical programs were retained, however, partially in order to comply with federal requirements. But the block grant component for 1995-1996 comprised $292 million (88 percent) rather than $247 million (77 percent) of total Community Aids funds. 7

In Minnesota, legislation was passed in 1995 permitting local governments and local nongovernment organizations to receive a consolidated block of state funds in place of categorical state aid programs. In order to achieve more coordinated delivery of services for education, child care, family services, child abuse, drug and violence prevention, and teen pregnancy prevention, the 1995 legislation allows counties, schools, other local governments, and community organizations to form collaborative agreements to consolidate all or some of the state funds that were previously received under separate program categories. The state will grant these collaboratives flexibility in spending these funds, provided that funds are used to achieve the goals of the separate programs and that outcome indicators are provided. In 1996, the state began to work with the first two collaboratives on implementation.

Consolidation of social services funds occurred on a smaller scale in Pennsylvania's Homeless Assistance Program. This program provides a mix of state and federal funds to counties for services to families in need of shelter or in imminent danger of becoming homeless. Program activities include emergency and transitional shelter, rental assistance, and case management services; before recent changes, each component was funded under a separate state categorical grant. Changes enacted in 1996 converted this aid into a block grant that gives counties the flexibility to allocate funds freely across any of these program activities. This block grant was funded at $21 million for the 1996-1997 fiscal year.

Ohio also converted several categorical aid programs for teenage pregnancy prevention into a single block grant to local government councils. The Wellness Block Grant, created in 1996, redirects categorical funding into a block grant for any county (or group of counties) that has formed a Family and Children First Council. The new block grant is intended to provide councils with maximum programmatic and fiscal flexibility while achieving the broad policy goals outlined by the state for reducing teenage pregnancies.

In addition to these enacted changes, the governors of New York and Connecticut proposed devolutionary changes to social services programs that were rejected by the state legislatures. New York's governor proposed a devolutionary shift for several social service programs in his 1996 budget request. The following three block grants to social service districts were proposed:

- The Home Care Block Grant would have subsumed a number of existing programs, including personal care, home/health nursing, the Long Term Home Health Care Program, the Consumer Directed Personal Assistance Program, and the Assisted Living Program. State regulations on counties would have been lifted to provide flexibility in designing and administering these services. The block grant would have cut state funding in 1996-1997 by about $75 million, 8 percent below its level in 1995-1996. The governor's proposal also would have eliminated the entitlement status of eligible recipients.

- The Integrated Delivery Systems Block Grant would have subsumed more than 70 separate funding streams to counties from the Office of Mental Health for services to persons with mental illness. Counties would have gained new flexibility and responsibility for the design and delivery of mental health services, although state funding would have been cut by slightly more than $100 million, a 14 percent reduction from 1995-1996.

- The Community Service Program Block Grant would have merged all state and federal aid related to alcohol and drug treatment and prevention programs. Under this proposal, counties would have been able to allocate funds flexibly across different services and would have been responsible for program planning and service provision. State funding would have been reduced by $30 million, a 14 percent reduction from 1995-1996.

None of these provisions were passed.

The governor of Connecticut included similar proposals in his 1995 budget for social services programs, and these also were not passed by the state legislature. The Safe Children Block Grant was a proposal to consolidate 12 programs for children and youth administered by five agencies into a block grant targeted to 15 high-need cities. Program activities funded under this block grant would have included youth training and employment activities, after-school programs, antiviolence activities, teen pregnancy prevention, mentoring, and tutoring. This block grant was intended to allow local flexibility in determining priorities, reduce the number of targeted cities from 27 to 15, and reduce total funding from $12 million to $9 million. The Human Services Block Grant, a proposal to consolidate 28 state programs administered by six agencies, would have provided funding for housing and homeless shelters, community and family support services (such as care for the elderly or disabled and substance abuse treatment and prevention), employment and training services, and medical care, health, and nutrition. Block grants would have been allocated to 15 planning regions. Total funding for the consolidated programs was to be reduced from $28 million to $21 million.

Finally, one state is known to have proposed a shift in responsibilities in the other direction — from the counties to the state. A bill considered by the Nebraska state legislature would have repealed county funding requirements for various social service programs, including mental health, substance abuse, developmental disabilities, and aging services. Although the bill did not require the state to assume funding responsibility for these services, the legislation was proposed with the explicit intent of implementing a recommendation by the Health and Human Services legislative committee that funding responsibilities be shifted from the counties to the state to relieve pressures on local property taxes. This legislation would also have shifted counties' responsibilities for the medically indigent and General Assistance to the state. This bill has been postponed indefinitely by the state legislature.

In summary, four states are known to have converted state categorical aid programs into more flexible funding for local governments: Wisconsin, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, and Ohio. New York and Connecticut considered proposals to create new block grants to local governments, with funding for the affected programs significantly reduced, but these proposals were not enacted. And in one state, Nebraska, legislation that would eliminate county funding requirements for various social services programs, with the understanding that the state would assume at least a portion of these costs, was considered but not passed.

Changing Responsibilities for Public Assistance and Workforce Development

Public assistance and workforce development encompass diverse programs with different opportunities for state-local devolution. The following sections briefly describe state capacities for decentralization and state-local shifts that were proposed or enacted in 1995 and 1996 in three areas: General Assistance, AFDC, and workforce development.

General Assistance

In contrast to AFDC, states have complete control over the degree of decentralization within their General Assistance (GA) programs. Because these programs are funded entirely by states and localities, there are no federal restrictions on the state-local arrangements chosen by states for the funding and administration of GA. Some states run a uniform GA program that is entirely state funded and administered. Other states require counties to have a GA program but give them control over program administration. In other states, there is no state-mandated GA program, but counties have the option to administer one using their own funds.8 Because states have complete control over GA programs, there were a number of proposed and enacted changes to GA programs during 1995-1996 that shifted state-local responsibilities.

The greatest shift in responsibility for GA during those two years was the change to Wisconsin's General Relief program. In the past, counties in Wisconsin were required by the state to provide General Relief to certain indigent persons, including both medical and nonmedical assistance, and state law established minimum monthly benefits for persons without income or assets. 9 A new law, implemented in 1996, replaces this mandated General Relief program with a Medical Relief Block Grant for Milwaukee County and block grants to all other counties for medical and nonmedical benefits. Although the state and local funding shares remain roughly the same as under General Relief (because counties are required to contribute funding in order to qualify for the block grant), counties are not required to participate in the block grant program. Also, state requirements specifying the types and amounts of General Relief benefits that must be provided by counties have been eliminated.

Pennsylvania also enacted a devolutionary shift in its GA program in 1996, although on a smaller scale. The state eliminated medical assistance to most GA recipients between the ages of 21 and 59 who are not disabled and who work less than 100 hours per month. Because medical treatment for these persons is no longer covered by the state, the state has provided $52 million in block grants to counties for behavioral health services for some of those formerly covered.

California enacted changes in 1996 intended to ease the burden on counties of funding General Assistance, because counties are required to fund and administer a GA program in accordance with state requirements. The following changes modified these requirements in order to decrease counties' financial burden:

- For counties obtaining approval from the state to decrease GA benefit levels, the time period for which the reduction would be in effect was extended from 12 to 36 months.

- Counties may limit GA eligibility for employable people to 3 months out of a 12-month period.

- Counties may decrease GA payments by an amount equal to the value of county costs of providing indigent health care.

The other major shift in responsibility for General Assistance was not devolutionary, but instead shifted control from local governments to the state. Before 1996, GA in Connecticut was the shared responsibility of the state and localities. The state paid 80 percent of benefit costs, and towns paid 20 percent of benefit costs and all of their GA administrative costs. Beginning in 1996, the state began paying 90 percent of benefit costs and assumed all administrative responsibilities in 10 cities. The state plans to take over GA entirely by mid-1998, with the possible exception of a few towns.

In addition to these changes, some proposals to realign state-local responsibilities for GA were considered but not passed. For example, before the Connecticut reforms, Governor John Rowland in 1995 proposed an Anti-Poverty Block Grant to replace state funding for GA with a fixed block of funds given directly to all municipalities to create their own assistance programs. The block grant would have been funded at $74 million, a $13 million reduction in state funding for GA from the previous year, but it was not passed. 10

Governor George Pataki's proposed 1996-1997 budget for New York included a similar initiative. He proposed an Indigent Medical Care Block Grant that would have provided counties with funds for health care services for state general assistance (Home Relief) recipients and other persons determined by the counties to be in need. This block grant would have replaced the state's Medicaid entitlement for persons receiving Home Relief and reduced state funding by about $125 million in 1996-1997, a 19 percent reduction. However, this proposal was rejected by the state legislature.

Finally, amid these devolutionary proposals, one other state besides Connecticut considered shifting responsibility for GA from localities to the state. In Nebraska, counties are required by the state to run a GA program, and they are responsible for program funding. As discussed earlier, a bill was considered in the state legislature in 1996 that would have repealed a broad set of county responsibilities for funding and administration of various health and human services programs, including the medically indigent and General Assistance programs. These proposed changes followed a recommendation by the Health and Human Services committee that the state assume responsibility for these programs to avoid duplication at the state and local levels and to reduce the demand on local property taxes. However, action on this legislation has been indefinitely postponed.

In summary, two states — Wisconsin and Pennsylvania — created new block grants in 1995-1996 to replace all or part of their former statewide General Assistance programs. One state — California — reduced county requirements for funding GA by granting counties additional flexibility to reduce cash assistance payments. In two states — New York and Connecticut — new block grants to local governments for GA were proposed but not enacted. And in two states, changes were enacted or proposed to shift major administrative and funding responsibilities for GA from local governments to the state. In Connecticut this change was enacted, but in Nebraska action on the proposed legislation has been postponed indefinitely.

Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC)

Before their replacement by TANF, state AFDC programs were administered by either the state or local government. Local involvement in AFDC varied in several ways, including the authority of local governments to appoint local personnel and the amount of assistance and administrative costs borne by localities. For certain aspects of AFDC, local governments could not be granted additional discretionary authority by the states because the states themselves were subject to federal restrictions. Federal AFDC regulations mandated that states provide cash benefits to families meeting eligibility requirements, and even those decisions that were left up to state governments (such as the maximum age of eligibility for a child) had to be applied uniformly across the state.

During 1995-1996 (before TANF replaced AFDC), few changes were enacted or proposed to devolve administrative or funding responsibilities for AFDC to localities. The few proposals known to have been put forth were in anticipation of federal block grants for welfare. For example, New York Governor Pataki's 1996-1997 proposed budget included several block grants to social service districts, 11 two of which would have devolved responsibilities for AFDC. These proposals were made under the assumption that federal welfare reform would be enacted before the start of the state fiscal year in April 1996. The first of the two block grants affecting AFDC was the Basic Care for the Needy Block Grant, which would have provided $100 million annually (after a 50 percent funding match by localities) to social service districts to provide non-cash assistance to persons becoming ineligible for assistance because of rule changes under welfare reform. The other AFDC-related block grant proposed by the governor would have given social service districts the opportunity to replace the current funding mechanism — an unlimited state match for all assistance and administrative costs, with the county and the state each paying 50 percent of the total — with a Local Option Block Grant. That block grant would have given each district the opportunity to receive state funding as a fixed payment in the form of a block grant, based on its projected needs. Districts opting for the grant would have been allowed to vary program coverage, benefit levels, and administrative procedures — subject to some state and federal requirements — and to keep half of the savings generated as a result of such changes. Both block grant proposals were rejected by the New York state legislature.

Similar proposals in other states were also considered but rejected in 1995-1996. In California, Governor Wilson's 1995 budget request included a provision that would have increased the county share of the nonfederal costs of AFDC from 5 to 50 percent. This would have increased county AFDC costs by about $1.2 billion; however, the governor's plan included additional state funding for trial courts and additional state revenue allocations to counties to partially offset this burden. Also in 1995, the North Carolina legislature considered but rejected a bill that would have eliminated AFDC for children born out of wedlock and created a block grant to counties to provide non-cash assistance to those children.

In summary, New York was the only state known to have considered a major shift in state-local responsibilities for AFDC in 1995-1996, in the form of block grants to social service districts. North Carolina also considered a block grant to counties, but only for those children made ineligible by a proposed family cap. A shift in state-local funding responsibilities was considered in California that would have increased the county share of AFDC costs, with some compensating assistance from the state. None of these proposals were enacted, however.

Workforce Development

In contrast to AFDC and state General Assistance, workforce development policies have historically been decentralized in all states. Much of the decision-making authority in the workforce development system rests with the more than 650 local Job Training Partnership Act Service Delivery Areas (SDAs), which are responsible for developing and implementing local job training plans. The states' primary responsibilities are to coordinate and integrate various workforce development programs, approve local SDA plans, and monitor program outcomes. Recently, many state workforce development systems have undergone restructuring, and the shifts between state and local responsibilities resulting from these changes are often complex. However, in only one instance is a state known to have shifted administrative responsibilities or funding mechanisms between the state and local levels.

The Texas state welfare reform legislation enacted in 1995 included a provision to increase flexibility for workforce development at the local level by consolidating training funds and creating a block grant to regional areas. The legislation consolidated funding for 28 federal and state job training and employment-related programs. These funds are allocated instead as block grants to newly created regional workforce development boards. These boards are responsible for the operation of training programs and are formed through the cooperation of local government leaders in each of the 28 designated regions. Before the board receives its workforce development block grant, however, the state must certify the board and approve its plan for the delivery of employment and training services. In the future (no sooner than September 1997), these boards may also receive subsidized child care funding from state and federal sources as a block grant.

Conclusion

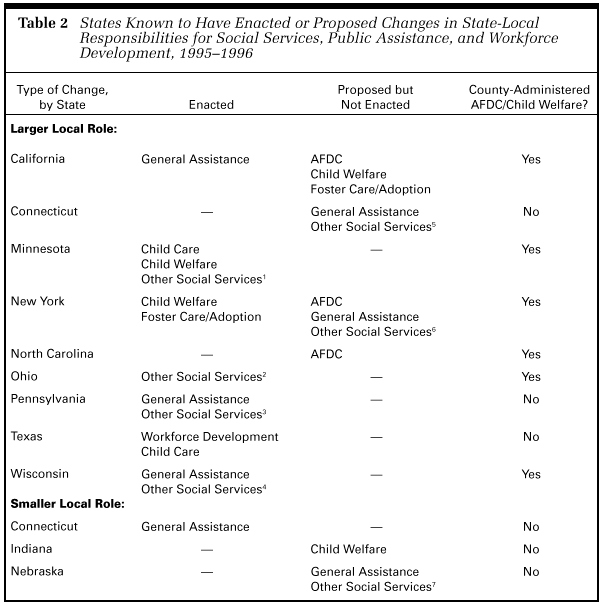

Table 2 summarizes the shifts in state-local responsibilities enacted or proposed during 1995-1996 and described in this report. In total, 11 states are known to have either enacted or proposed a shift in funding or administrative responsibilities in the areas of social services, public assistance, or workforce development. Eight of those states enacted legislation. In almost all cases, changes were intended either to shift responsibilities from the state to localities or to relieve a state mandate that local governments administer or fund a program.

These devolutionary changes were in contrast to a lesser number of initiatives that shifted program responsibilities from local governments to the state. Only one state — Connecticut — enacted such legislation. Proposals in Indiana and Nebraska to increase the role of the state while reducing county responsibilities have not been passed by state legislatures. Therefore, although only a few states enacted devolutionary changes and several of those changes were made to relatively small programs, the overall trend for the states known to have altered state-local responsibilities in these program areas is toward devolution.

Known changes in state-local responsibilities were enacted primarily in General Assistance and assorted social services programs. These are the areas in which states had the most autonomy and freedom to structure state-local responsibilities during 1995-1996, either because these programs are state funded or because at least a portion of federal funding for these programs is in the form of a block grant. In a few states, changes to AFDC were proposed in anticipation of the federal block grant for welfare, but none of these proposals were enacted. Changes in workforce development programs detectable through an examination of funding and administrative shifts occurred in only one state, Texas. This may be because workforce development systems were highly decentralized before 1995, so that further devolution was viewed by states as unnecessary.

It appears from this analysis that states with the most decentralized systems — that is, those with county-administered AFDC and child welfare programs — are the most likely to propose or enact changes to further shift responsibilities from the state to the counties, or to relieve counties of some program requirements through mandate relief. Although there are only 13 such states (see Table 1), more than half of the states known to have enacted or proposed changes in 1995-1996 have county-administered programs (see last column of Table 2). Of the 36 states (including Washington, D.C.) with state-administered systems, only 5 are known to have proposed or enacted shifts in state-local responsibilities, and in 3 of those states (Connecticut, Indiana, and Nebraska) at least some of the changes were intended to shift responsibilities in the opposite direction, from localities to the state. (Neither of the two states with mixed state-county administration is known to have enacted or proposed any changes.)

There are two related reasons why states with county-administered AFDC and child welfare systems may be more likely to enact or propose devolutionary changes. The first is that in these states local governments already have administrative and funding structures in place that allow them to assume greater responsibilities. For example, a county responsible for AFDC and child welfare already has the human and physical resources, expertise, and organizational structures needed to administer these two programs; presumably some of these same structures could be used if responsibility for additional programs were devolved from the state. In states that administer AFDC and child welfare programs directly, without county involvement, counties may not be as able to assume new responsibilities for other types of programs. The second reason is that certain shifts in state-local responsibilities are adjustments to arrangements for local administration that are already in place. For example, counties will only contribute directly to funding for a program if they are involved in its administration, so changes in the state and county shares of program funding will only occur in states where counties have some administrative responsibilities.

Although it is premature to draw strong conclusions about how state-local relations will change in the coming years, the 1996 federal welfare reform legislation will likely be a catalyst for further state-local devolution. By replacing AFDC with TANF, the federal government has made it easier for states to integrate their public assistance programs and perhaps to achieve greater decentralization, as has already occurred in several states with General Assistance. In the wake of federal welfare reform, as states further restructure their public assistance programs — and perhaps their social service and workforce development programs as well — they will have additional opportunities to reconsider the role of local governments within those systems and to make decisions about where funding and administrative responsibilities should rest.

Notes

1. TANF does not reduce the level of federal government spending as compared to the programs it replaces. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the conversion to TANF will increase federal spending by about $3.8 billion between 1997 and 2002.

2. In 1992, state aid to local governments (including assistance to schools) was 32.3 percent of total state spending. This was the lowest proportion in any year since the U.S. Census Bureau began reporting these statistics in 1957. Before 1989, aid had never been less than 34 percent of spending. For a review of state policies between 1990 and 1993, see Steven D. Gold and Sarah Ritchie, "State Policies Affecting Cities and Counties in the Early 1990s," Public Budgeting and Finance (Summer 1994).

3. According to the Census Bureau, local taxes rose faster than state taxes in every year from 1985 to 1992. This trend did not continue in 1993 and 1994. In the latter year, Michigan's school finance reform caused the national total of state taxes to increase faster than local taxes.

4. Direct changes in state Medicaid programs are generally not included in this report, although changes to some programs that may be financed by Medicaid (for example, home health care or mental health services) may be included if they are part of a broader set of changes to social services programs.

5. Fiscal Survey of the States, National Association of State Budget Officers and National Governors Association; State Legislative Summary, National Conference of State Legislatures; Coast to Coast — News from America's Counties, National Association of Counties.

6. The sources for this information on funding levels are the Statistical and Narrative Summary of the Executive Budget and the Report of the Fiscal Committees on the Executive Budget, both published by the New York State Legislature. Roughly half of the funds cut in 1995 were due to non-compliance sanctions placed on local districts by the state (unrelated to the new block grant), and part of the increase in funding in 1996 was due to the restoration of funds when the sanctions were removed.

7. The Community Aids allocation for 1995-1996 was increased to $334 million.

8. See Cori E. Uccello, Heather McCallum, and L. Jerome Gallagher, "State General Assistance Programs 1996," The Urban Institute, October 1996.

9. The exception is Milwaukee County, which stopped providing nonmedical assistance in 1995 independently of the new statewide changes.

10. In a related proposal, also made in 1995 and rejected by the legislature, Governor Rowland proposed a Tax Relief Block Grant. This would have replaced the current system of reimbursement to local governments for tax relief programs for the elderly and disabled with funds allocated to 15 planning regions. Each region would have been free to determine the type and amount of tax relief to be provided for the elderly and disabled. This proposal would have reduced state tax relief from $54 million to $41 million.

11. There are 58 social service districts in New York: New York City and 57 counties.

Tables